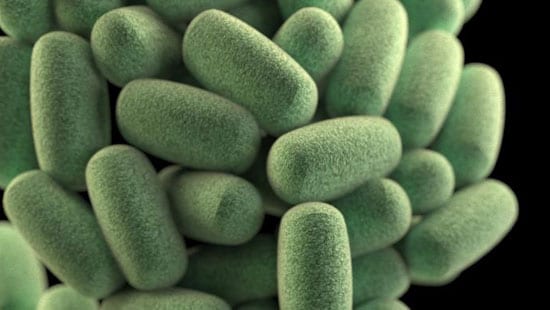

Clostridium Perfringens

As part of our company-wide commitment to making your business - and the world - cleaner, safer and healthier, Ecolab will work with you to find solutions that help solve your food safety and contamination issues.

Photo courtesy of: CDC/James Archer

WHAT IS CLOSTRIDIUM PERFRINGENS?

Clostridium perfringens causes a relatively mild foodborne illness after the ingestion of many organisms that produce toxins in the gut. There are 5 types of toxins, denoted as A-E, with types A, C, and D pathogenic to humans. C. perfringens is a sporeforming organism, with spores very widely distributed in nature and in the intestinal tracts of animals and humans. Spores commonly contaminate foods. That fact alone is not concerning, but with temperature abuse of the food, the spores can grow to large numbers, with potential to infect humans.

Perfringens poisoning continues to be one of the most commonly occurring foodborne illnesses per the US CDC, but much may go unreported, since stool cultures may not be routinely cultured for C. perfringens cells.

WHAT ARE THE SYMPTOMS?

Abdominal cramps and diarrhea occur in 8-22 hours after consumption of large numbers of C. perfringens cells (>106/g) in food that can produce toxin. Recovery happens in 24-48 hours. Complications can include dehydration or death in rare cases.

A more serious effect of C. perfingens toxin type C is thought to cause “Pig-bel syndrome” resulting in necrosis of the intestines and septicemia and can result in death. This is extremely rare in the US, but has occurred more commonly in developing countries, especially among malnourished people who have sudden dietary over-indulgence. It has been associated with children who live in New Guinea after traditional pork feasts, and less frequently among adults who have developed some immunity.1

[1] Skjelkvale & Duncan. 1975. Characterization of Enterotoxin Purified from Clostridium perfringens Type C. Infection and Immunity 11(5): 1061-1068.

HOW IS IT TRANSMITTED?

Temperature abuse is the primary route of transmission. Contaminating spores in a food product will be activated with heating through a cooking process and be able to grow to large populations, with maximum growth between 98°F (37°C) – 117°F (47°C) and under conditions of low oxygen (such as in the interior of a piece of meat or below the surface of a stew). Slow cooling of cooked foods, especially meat containing items or gravy, have been linked to outbreaks. Turkeys cooked for large groups of people, then left out at room temperature for an extended time (e.g., on a buffet) are possible vehicles for the organism.

Person to person transmission does not occur.

HOW IS IT CONTROLLED?

Control relies on proper storage and cooling of cooked foods. Foods should be cooled quickly especially through the range of 135°F (57°C) to 41°F (5°C). It is possible to kill growing cells if the food is reheated above 158°F (70°C). The US Food Code outlines cooling requirements in a step-wise process from 135˚ (57°C) – 70˚ F (21°C) within 2 hours, then 70°F (21°C) – 41°F (5°C) in next 4 hours, and that foods which are reheated reach a temperature of 165°F (74°C).

C. perfingens needs to be controlled in commercial meat processing as well. The USDA-FSIS requires that processors of various cooked meat items cool these items adequately to prevent the growth of spore-forming bacteria. The regulations apply to ready-to-eat roast beef, cooked beef and corned beef products, fully cooked, partially cooked, and char-marked meat patties, and certain partially cooked and ready-to-eat poultry products. Processors may follow prescribed cooling regimens or validate their own processes to guarantee the safety of their products.

References

1. International Commission on Microbiological Specifications for Foods. Microorganisms in Foods 5, Characteristics of Microbial Pathogens. Blackie Academic and Professional, New York. 1996. pages 112-125.